“If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere.”

Theresa May

Historically, being a non-Republican state, colonial Britain had subjects rather than citizens. Time of course stumbles on, as do stubborn common-sense habits and laws. Rather than an encyclopaedic ambition to make sense of any of this, the three painters in this show simply manifest the edges of contemporary life’s manifold circuses. It might be easy to dismiss their works as mere carnivalesque drollery, but no, weighty realism insists within the uncomfortable levity. Here, laughter is a form of self-defence and masks (thereby revealing) actual vulnerabilities; real subjectivities are invented.

Jesse Wiedel lives and works in Eureka, California, and his paintings develop a dystopian nightmare vision of countercultural breakdown in that rural habitat of drug victims, just about inhabiting sickly religious and other mad delusions. Aliens and alienation stalk the land on BMX bikes ridden by prematurely aged methamphetamine visionaries. Entropic sourness infects his paintwork – there is no ‘outside’ to this sprawling hopeless habitat, which indeed feels theologically cosmic in scope.

Charles Williams might seem to hail from somewhere far away from such enervated horror and bad survival strategies, and yet even in one of England’s home counties, sun blasted Kent, there is infection underlying the relative NHS guaranteed gentility. Freakishness rears its head in the form of Williams’ odd animals, hinting at a kind of queasy animation, all treated with Delacroix-like painterly mastery that only adds to the incongruity. Williams is developing into a master colourist and yet, rather than decadent aristocratic Shakespearian and Orientalist romantic fantasies from lost empires, his eye is cast on local subjects. He doesn’t resist his caricaturist eye – the graphic crudities of Gillray and Rawlinson insist from beyond the 19th century, despite the refined paint passages that he expertly deploys.

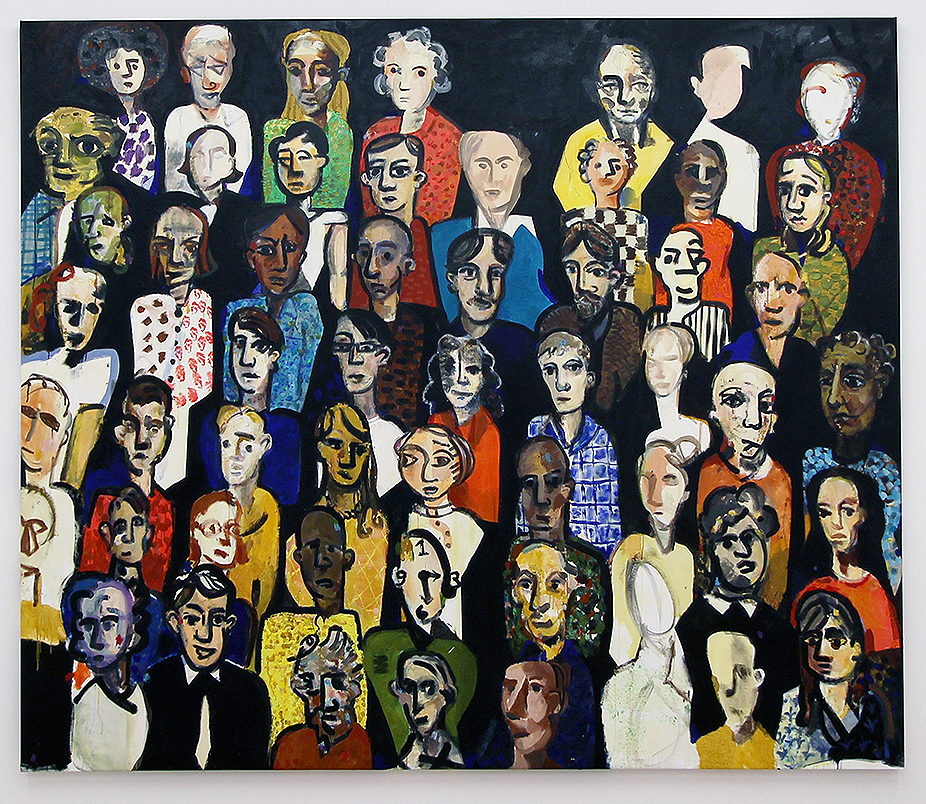

Phil King ranges far and wide, a reluctant world citizen, and he too presents populations – half recognisable personages – paintings as leftover bits and pieces of grand projects. Dysfunctional crowds, (he painted a morbid Question Time audience artificially populated by deadly red-faced right-wing goons sitting uncomfortably alongside late great artists etc). He is currently struggling with a painting of the 2020 Cheltenham Racecourse crowd as the spread of deadly contagion in that officially sanctioned mass spreading event took hold. King’s work is a kind of history painting defined by partial, fragmentary, sensibilities. Horatio Nelson effigies and half recognizable film stars rub shoulders. His is an art of lookalikes and yet sometimes even that definition dissolves in painterly blur.

It might all seem to take the horrible and the awfully failing as humorous motif and thereby to stroll inappropriately beyond the pale, but participation in sanguine realism is not only a form of resistance but is also hopefully empowering, and these painters (both citizens and subjects) are great exemplars of it – while simply offering us unlikely ‘good paintings’.